Editor’s note: This article is part of a larger report, Healthcare’s $1 Trillion Challenge, which provides a roadmap for creating a more affordable and sustainable healthcare system. Discover further chapters on reducing clinical labor intensity, relieving administrative burden, and curbing the impact of growing drug costs.

It’s become a familiar trope domestically and even around the world: US healthcare has become exceptionally unaffordable — for everyone.

Over half of adults under the age of 65 report having difficulty affording healthcare costs. And by 2035, out-of-pocket expenditures for the average American will rise to $2,500 per year, up from roughly $1,450 now. Taking a broader view, national health expenditures are expected to double to $9 trillion by 2035 and will represent one-fifth of the entire US economy.

The industry has been down this road before. In response to escalating costs in the 1990s, regulators and industry stakeholders were pressed to make deep spending cuts. Although the Balanced Budget Act (BBA) of 1997 was projected to save billions of dollars in federal expenditures through cuts to providers and insurers, as well as increased cost sharing for beneficiaries, it further stressed industry players with thin margins and contributed to an unsustainable trajectory of employer-sponsored insurance. Consumers have ultimately borne the long-term impact of some of that, with the average deductible for single coverage increasing by $1,151 from 2006 to 2023. History has shown that this form of reactive, last-ditch cost cutting is painful. In fact, many of the BBA’s provisions ratcheting down payments were undone a couple of years later.

There is a better way forward. Using our unique vantage point in the industry, a previous Oliver Wyman report mapped out the direction of travel for the future of healthcare in 2035. We identified areas with significant potential for change over the next decade-plus.

This report builds off that work and details what the industry needs to do to sustain a new and better healthcare system. We outline a course for the industry to save over $1 trillion in 10 years. To get to that future, the industry needs to look different and operate differently, and leaders need to a set a new course and speed — one in which cost growth begins to slow or even declines. In this report, we are not shying away from the elephant in the room: affordability.

Achieving $1 trillion in savings for sustainable healthcare

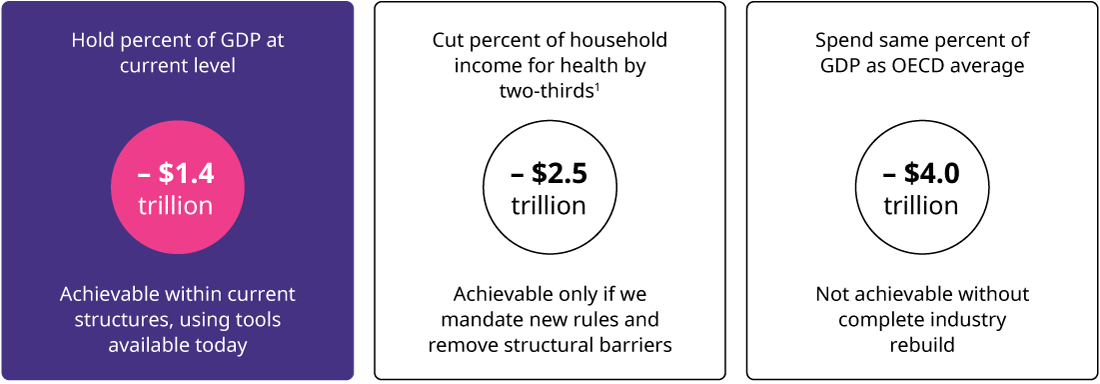

An unchecked future will lead to crisis — but what affordability target should the industry aim to achieve? One approach is to benchmark against current performance. Although flawed, the current system is stable. The industry could recommit to affordability by aiming to keep healthcare costs as a percentage of the US economy stable over the next 10 years. That would require $1.4 trillion in savings by 2035.

Another approach is to anchor on affordability for consumers. Americans are struggling to afford healthcare costs. In 2035, healthcare could compose about 30% of household income for those with private insurance. Reducing that to 10%, which is a slightly more manageable percentage of household income, would require a herculean effort to save $2.5 trillion in 2035.

A more ambitious target would compare the US to its peers. US healthcare has long been criticized for being significantly higher cost than in other industrialized nations. Using Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) estimates, US healthcare spending would need to represent only 11.8% of the economy by 2035. That would require cutting $4 trillion, a feat only possible if the entire system were restructured.

Tapping into existing tools, pilots, and experiments that are currently in the market, the industry could achieve close to $1.4 trillion in savings and hold healthcare spending constant as a percent of gross domestic product. This is within the scope of what individual players can achieve in today’s environment. The $1.4 trillion target acknowledges that some cost growth is inevitable in a privatized system, and it doesn’t tie the industry to international benchmarks that don’t account for US-specific dynamics. But it’s still a meaningful departure from the current spending trajectory and lays the foundation for bigger cuts in the future.

The chapters that follow highlight the most important levers that can help the industry achieve these savings.

Removing structural barriers to build a better healthcare system

While $1.4 trillion is a good start, we can achieve more and get closer to even greater benchmarks if stakeholders are willing to move beyond existing tools and begin to reimagine the embedded structures of the current industry. While we excluded major systemic changes, like moving to a single-payer system, from consideration for this analysis, there are many other policy and regulatory changes that could unlock new efficiencies and cost savings. For example, mandated standardization of administrative processes or consistent payment reform policies could align players across the industry and reduce low-value variation. We explore several of these changes and their wide-reaching implications in the following chapters.

Three key factors driving up healthcare costs

National healthcare expenditures are forecasted to grow by almost 6% per year over the next dozen years. The industry needs to identify and target the key drivers of spending growth to disrupt this trend.

Historically, the industry has dedicated significant time and energy to managing utilization of care to control costs. The last two decades have seen a renewed focus on chronic care management programs, value-based care or risk-sharing contracts, and preventive care, all with the aim of rightsizing utilization and improving affordability. But while US healthcare spending per capita is almost twice that of other OECD countries, utilization rates in the US do not differ significantly. The US has a below-average length of stay, fewer inpatient discharges, and fewer physician visits per capita than comparable countries. High utilization alone does not account for growing US healthcare spending.

The aging population is another candidate for escalating healthcare costs. By 2030, for the first time in US history, people aged 65 or older will outnumber those below the age of 18. These demographic changes will require operating models to meet the needs of seniors, but they are only responsible for about 20% of the projected growth in costs. The much larger driver is unit cost growth, or the cost of delivering and consuming care.

This is actually good news. It means the industry has the power to influence major buckets that are driving spending increases. We zeroed in on three high-cost areas:

Labor intensive processes impacting healthcare industry efficiency

Nearly every care encounter delivered today requires multiple people, many of them highly trained clinicians. Too often, these resources are not used correctly — they’re bogged down with administrative or low-value tasks that prevent them from operating top of license. By 2035, healthcare will need to add new jobs at four times the rate of the rest of the economy. This is unsustainable. The industry must take action to reduce the labor intensity of care delivery.

Growing administrative expenses strain efficiency and drive costs

Healthcare is not achieving efficiency with scale. The administrative cost structure continues to grow at the same rate as clinical spending. In addition, new innovations frequently add administrative burden, offsetting the cost savings. Medicare Advantage, for instance, has spurred transformation in care models and patient engagement but has also driven the expansion of expensive, labor-intensive coding and quality reporting functions. Healthcare leaders must break this cycle and bend the curve on administrative costs.

Rapid growth of drug spending drives systemic cost challenges

The growth of high-cost specialty drugs has been rapid — specialty drugs now represent over 50% of annual drug spending, up from 27% in 2010. The trend is expected to continue in the next decade. While medications are generally more cost-effective than human interventions, this increase is not displacing any existing medical spending. In fact, it is adding costs, compounding the problem. Without action, high costs will spiral the system into a crisis — or limit access to a select few.

The industry will need to make big changes to bend the cost curve on these trends. This won’t be — and can’t be — win-win for everyone. But some pain is necessary to avert the coming crisis and unlock better access and outcomes for all.

Driving innovation now to transform healthcare industry

The industry has demonstrated the ability to make changes when under pressure. A tremendous ability to innovate was showcased during the COVID-19 pandemic: Vaccines were developed in record time. There was rapid expansion in telehealth. Care was moved to more optimal settings.

Additionally, various pilots and experiments have demonstrated that innovations in legacy processes, staffing models, and pricing methods can lead to significant savings without jeopardizing outcomes. In addition, new tools will open new opportunities. The promises of artificial intelligence and new diagnostic tools can transform what is possible and reconstruct entire sectors of work and pathways of care.

Why reducing healthcare costs now is vital for our future

An affordable system is not only the right thing to do for patients. It will also offer new pathways to value and sustainability, and new ways to compete in an evolving market. Too often, today’s business models rely on hidden fees and undifferentiated services that are vulnerable to competition, innovation, and cost pressures. As cost pressures increase, affordability will become table stakes to compete successfully in the future. Driving toward this savings target needs to become the top agenda item of every player across the ecosystem.